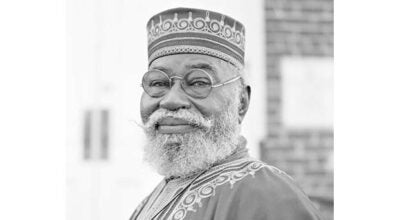

Daughters Remember Rev. L. Francis Griffin

Published 5:48 pm Thursday, May 22, 2014

FARMVILLE —The youngest daughter of The Rev. L. Francis Griffin would have started school in the fall of 1959.

It was a different world.

A segregated world.

Cocheyse, or “Cookie” as she is called, was told by her dad there would be no school.

Sister Naja remembers how her sister, who wanted to go, cried.

Prince Edward County’s public schools, in the throes of a legal battle and a divided community, would never open that year. Or for five years, in all.

While Prince Edward’s role is forever etched in the historic Supreme Court’s Brown decision that ended segregation in public schools, its follow-up, the Griffin case, forced the reopening of schools in Prince Edward.

After a five-year battle following the Brown decision and a series of appeals that led the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, it was finally over. There would be open, integrated public schools in Prince Edward.

Cocheyse, by 1964 at age ten, would finally get to go to the public school.

While 16-year-old Barbara Johns was the sparkplug that launched what would become the Brown case, it was Rev. Griffin who carried its torch. It is, in fact, several of his children who are on the court document in the Griffin decision. Listed alphabetically, Cocheyse is first.

“…I tell people all the time, circumstances of birth and, as much as I wanted to go to school, the court case is truly about my parents and the sacrifices that they made and that my name being associated to the case is just an extension of their dedication to see this battle through from beginning to end,” Cocheyse “Cookie” Griffin-Epps said Saturday during her visit.

Cocheyse and her sister Naja Griffin-Johnson, were among those attending the special NAACP program at the Moton Museum commemorating the 60th anniversary of Dorothy E. Davis et als v. County School Board of Prince Edward County — the Supreme Court decision that declared separate and equal as unconstitutional. (The case, wrapped in with others, is more commonly known as the Brown decision). But the program also highlighted the 55th anniversary of the closing of the public schools in Prince Edward to avoid the Davis decision, and the 50th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision in Cocheyse J. Griffin, et als, v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, which effectively declared if the County did not operate public schools there could be no public schools in Virginia because it was a denial of equal protection of the law.

“…I think it’s an amazing thing. It is not something that I take lightly, but I don’t think it’s something that places me on a pedestal either,” she said.

When she looks at the overall picture, she thinks it’s the divine order of things.

Her birth order.

Her name.

The case.

The year she was born, 1953.

The year she was due to start school, 1959.

“…To me, it’s like that plan was put into place long before I was born, long before my father came back to Farmville,” she says.

Perhaps, looking back, it was a series of events that simply were meant to be.

Rev. Griffin grew up in Farmville. His father was ill in 1949 and he and his young son and wife came home for a visit. While here, the elder Rev. Griffin, pastor of First Baptist Church, passed away.

The church asked Rev. L. Francis, who had been leading a church in New Jersey and finishing his course work at Shaw, to fill his shoes. He agreed.

It wasn’t long—the spring of 1951—when a group of students led by Johns, upset with the inequality of their school, went on strike for better facilities. Encouraged by the NAACP, local families would eventually file suit in what would become the Davis case. When the Supreme Court struck down segregation, Prince Edward, as did other localities, dug in its heels. Rather than integrate, however, they took the extraordinary step of closing public schools.

Which eventually led to the Griffin case.

“I didn’t know about all the other kids,” Cocheyse reflected. “I didn’t care about all the other kids, but I knew that this court case came about because my daddy was gonna make sure that I went to school.”

She adds that she knows that her dad wanted to make sure that every child in Prince Edward County was able to go to school.

“…All I remember is my father fighting for the justice for the kids in Prince Edward County. That’s what we grew up with in our house. That’s all we knew. So we didn’t know a different life. We didn’t know we could have a father who was there all the time. He was often on the road speaking, often going places to raise money…to tell the story of Prince Edward County. So we thought that was like a normal childhood,” Naja would offer to the group gathered for the program after a tour of the museum. “He would say to us also that he loved us dearly, but he said ‘as much as I love you, I love every child in Prince Edward County. So don’t ever feel that you are any different than everybody else—that I’m fighting for you, but I’m fighting for all the children.’”

Education was preached in the Griffin home. Books were everywhere. The first year the schools were closed, Cookie and Naja went to New Jersey and stayed with their grandmother.

“And then he brought us back because, once again he said, ‘if…there are so many kids out of school in Prince Edward County and I want you all back here, you know, ’cause I’m fighting for everybody and I want you here,’” Naja said. “And our mother was a teacher so she home-schooled us. But…he loved to read and I mean this man would be reading four or five books at a time.”

Eventually, every room in the house became a library.

“It’s like, you know, he never backed down. I don’t care how hard they made life for him—and people tried to make it very hard, some black people and some white people…some black people who felt he was causing trouble and gonna stir up stuff that didn’t need to be stirred up and so they kind of turned their backs on him and my mother and…the white people …like who owned stores and stuff would, like, not extend credit to him.”

He was a country preacher and, though they didn’t have money, they didn’t suffer.

Naja thinks of her dad’s strength and conviction.

“…Until he took his last breath, it was really…just about fighting for justice,” she said. “And if I say he gave his life for the fight, I think he gave his life for the fight because there are times we would tell him you have to slow down, you have to start taking it easy because (of) your health. And he said that he would die fighting for Prince Edward County, and he did.”

Cocheyse says that the most enduring memory of her dad (who passed away in 1980) is the quality of time that they spent with him. He was just a man, a daddy.

Sometimes, she reflected, he would take the phone off the hook, sit down and read with them, draw silly pictures, teach them card games.

“If we were really good, did everything that we were supposed to do, he would dance the “hucklebuck” for us. I mean…he was just a daddy…And a good daddy,” Cocheyse reflected.

And he wasn’t just theirs—he had reached out to other children along the way. Many who depended on him for emotional support.

He taught them all what family dynamics were all about.

“He loved his family dearly,” Cocheyse said.

She noted, “I can remember as a young girl my mom made him a Santa suit and he would ride from community center to community center and give away toys and a girlfriend of mine and I used to dress up as his elves and he would play Santa. And I remember hearing … when we made a stop, one little boy said, ‘See, I told you Mr. Rev. Griffin was Santa Claus.’”

The memory evokes a chuckle.

He was their hero, Cocheyse says.

“…I didn’t worry because when he promised us we would go to school, we would go to school and we would go to school in Prince Edward County,” she said.

Cocheyse remembers being told of the court decision, in a happy way. Their dad would dance, telling them they were going to school. That it was over.

“…It was just a big celebration ‘cause it just felt like we won, you know, and not just we won the right to go back to school,” Naja said.

Cocheyse and Naja both attended the free schools the year before the schools reopened. Cocheyse is the first from her family to graduate from Prince Edward. The American Friends Service Committee placed Naja first in a school in Los Altos and then Palo Alto, with white families. The first was an all white high school, where she was not that embraced; she went back to the American Friends Service Committee which moved her to a more integrated in a mixed community, which was very good.

There’s a blessing in every storm, she says, quoting her grandmother.

There were some positive things that happened.

Cocheyse attended college, but did not graduate. She got married, moved around in support of her husband’s career and works for a major international insurance company. She lives in Columbia, Maryland today and has been quietly involved in community and church.

“I can’t say that I had an extraordinary life, I had an ordinary life,” she says.

Naja still lives in Los Angeles. She, too, attended college, got married and since divorced. She has two children, one that writes for television and a second who works in finance, and grandchildren, too.

“I think my life is rich. I feel it’s full,” she said. “I involve myself in a lot of community activities. Politics, I…am forever campaigning for somebody…”

There will, however, always be a connection here. And they love coming back and the people as well as the town.

Their dad, Naja highlights “always taught us…not to hate anyone, that everybody has a reason for feeling the way they feel and it’s not always the right way, but he said…they’re entitled to their feelings. You cannot make a person feel, but he said it’s like by law this is what should be…He said…‘I’m not necessarily fighting for integration, I’m fighting for justice and…there’s a difference.’”

They certainly see a difference in the town they grew up in. There’s the Light of Reconciliation burning brightly in the courthouse bell tower. (Naja offered that the ceremony was very moving.)

Far from the days of divided neighborhoods where children riding their bikes couldn’t cross invisible lines.

Or the days when her mother would get threating phone calls at night, being told that her husband wasn’t coming home, that he had been killed. And having no way to verify until he called or came back.

Through it all, they were taught not to hate or be fearful.

“It’s pride because I know what sacrifices were made by my parents in order for that to all come to fruition…It was a struggle,” Cocheyse cites of being connected to the case. “And I know—I may not have known then, but I know now.”

It’s not because her name is on the court case, she says, but because her daddy sacrificed and gave his entire adult life to the Prince Edward cause and her mother quietly supported him.

“It’s like seeing Griffin Boulevard when we come here. Like, we lived on that street, we knew it was Ely Street…When we see Griffin Boulevard, it does give you a sense of like pride that in the sense that…they’re honoring our father for what he did,” Naja said.

Naja explained to her children, who are now in their 30s and 40s, that they are the first generation in their family that have no restrictions on their life.

Her grandchildren perceive such issues to be hundreds of years ago, not one generation removed.

“When we come here we see black people living in neighborhoods we knew used to be primarily white or white people living in houses of friends of ours who were black or we see integrated couples or we see bi-racial children. I mean…I never thought we’d see (that) here and so I just think it’s like there’s just so much hope, you know.”

Naja and Cocheyse toured the historic museum and its displays before kicking off the program. They both enjoy coming back to Farmville.

“My father always said he wanted to have a place where the story of Prince Edward County would be told. He wanted school kids to be able to know the history,” Naja offers in the program. “For years, he used to say, when I’m long gone, I want a place where the story will be told.’”

Naja adds that she knows he’s smiling.