The 1972 Agnes Flood: Denial Became The Nile

Published 4:08 pm Tuesday, June 19, 2012

FARMVILLE – With the water rising, 25-year old Jimmy Hurt lay down to rest on a check-out counter. He woke up with water picking his pockets and fingering the cash register.

The summer solstice 40 years ago should have filled the sky with more light than any other day of the year. It was filled with the most floodwater in the history of Farmville, instead.

Wednesday, June 21, 1972 was one of Noah's forty days.

And one of his ark's forty nights.

Twenty-six straight hours of rain from Tropical Storm Agnes almost washed the light away.

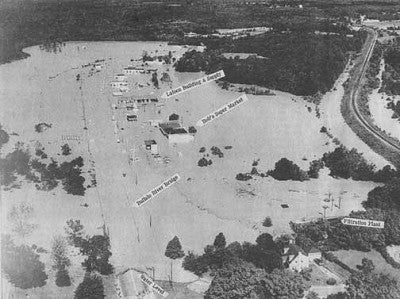

The Appomattox River would crest at 29.7 feet, 13.7 feet over flood stage, still a Farmville record. Businesses were inundated, factories closed, families isolated and highway traffic into Farmville shut off from the west and the north.

The National Guard was called out and patrolled by boat behind buildings, some of which had been looted.

“The day it was all unfolding, I must have been in great denial because I didn't think it could possibly happen,” Jimmy Hurt told The Herald on Monday, remembering.

From denial, reality sank in, soaked and sodden, a rain of Biblical proportions as over seven inches fell in Farmville, with even more upstream.

Boat travel was possible on West Third Street down from the hospital in front of Bob's Super Market, owned by Hurt's father and the store's namesake, but forget driving.

West Third Street (aka Business 460) was submerged for three-quarters of a mile, from the hospital to what was then the Kit Carson Motel, with Bob's Super Market smack dab in the middle of the flooding.

At one point during that Wednesday night, Hurt and two colleagues who'd decided to ride the storm out at the store, while putting higher value items on upper shelves, gave up the fight to nap on the store's three check-out counters.

The water was knee-deep when they closed their eyes. “Hours later I awoke to find myself lying in water,” he recalls. “The water had reached the top of the check-out counters and had entered the cash register drawers.”

He stood up in water just over his waist.

“Nothing like that had happened in my lifetime,” Hurt said, recalling the feelings he had as a 25-year old with Hurricane Agnes approaching in 1972, getting weaker, becoming downgraded. “Why all this commotion? It can't happen. It's not going to happen.”

It happened.

“Right till the time the water started crossing the highway and come up in the parking lot I was still thinking it's not going to get up this far into the building.

As I was thinking back on it I was thinking,” he said, “Man, I must have been in denial.”

In denial and then in the Nile. Or water so wide and deep it looked like the Nile.

“It was quite a bit of stir about it the day before and I just tended to disregard (Agnes),” he said, smiling and shaking his head, 65 years of life experience under his belt today.

Looking back 40 years, what registers most from Agnes' downpour was “the outpouring from the community” in the wake of the flood, he said. “People I didn't even know-and I knew just about everybody in town in those days-people from everywhere were showing up with shovels, wheelbarrows, boxes, plastic containers and helped clean up.

“…The whole town pulled together. It was heart-warming, something I had never seen or experienced in the town before,” he said. “Everybody was pretty much touched by it but then everybody pulled together in a way I'd never seen before. And that went on for a week or ten days…Just the everyday person off the street came to our store, that I had never even knew, to help. Everybody wanted to do their part.”

After the floodwaters receded, something was left behind, along with stains and debris. “I guess it gave me a little bit of a different outlook on the community after that,” he reflects.

The night the flooding began, Jimmy Hurt and two colleagues felt no fear inside Bob's Super Market.

“I wasn't scared and neither were the guys with me. Even the next morning. We weren't scared. We were more in a playful mood,” he said.

How did that playfulness show itself?

“The night we were in there working we were also getting in the beer case and enjoying some beer and eating potato chips. And the next morning we got up and drank a few more beers,” he said. “I think we were all just in shock. And I can't ever remember being stunned like that. But after we had a round or two of beer we went outside to play in the water.”

A popular past-time in 1972 was hot-rodding around the Tastee Freeze on West Third Street.

“So I decided to be the first one to swim around the Tastee Freeze, so I swam up Third Street and around the Tastee Freeze and back,” Hurt relates.

“It wasn't dangerous. Anytime you wanted to stop swimming you could stand up and it was about up to here,” he said, pointing to a spot just a couple of inches below his chin.

The flooding that morning was different than he might have expected.

“I think a lot of people thought of a flood as rushing water going through town and as it turned out the water backed up from the Appomattox River and came up Grosses Branch and right up the Buffalo River and just backed in,” he recalls. “So everything was just still and quiet.

“Eerie.

“I'm just so used to hearing the traffic coming by, the hustle and bustle of everything. The first morning when I eased out into the parking lot,” the water nearly neck high, “there was silence everywhere.

“A different feel to everything,” he said.

Despite the absence of fear, Hurt remembers that “once the water started coming into the store I felt out of control. I was used to being in control of everything and all of a sudden we were at the mercy of the water….

Out swimming and playing in the floodwater on Thursday morning, June 22, 1972, Hurt saw there “was a lot of stuff floating around, like propane tanks and drink boxes and all kinds of stuff. I was watchful for snakes. We did see a few dead animals float by. Everything was getting swept down toward the river but it wasn't really rushing down. It was all just standing still.”

They weren't supposed to be there, of course, in the flooded store or playing in the flood water.

“We had no idea anyone would come along and catch us outside. We knew we weren't supposed to be in the area,” Hurt said. “We had been told to evacuate.”

But they were spotted and “told to go back and wait by the store and somebody would come by and take us out of there,” he said.

They did and they were.

Bob's Super Market had to throw out more than $100,000 worth of food, about $1 million in today's dollars. (Damage town-wide was $4 million in 1972 dollars).

The business was the first grocery store to reopen in Farmville following the 1972 flood, after getting Health Department approval to do so. For a week, town residents had to shop out of town for food, if they could get out.

“It was a helluva situation,” Hurt said.

And it changed the 25-year old.

“It made me realize that overnight terrible things can happen. You can get wiped out,” he said Monday, forty years later. “Things got a little more serious in my life, I would say. That's it in a nutshell. The seriousness of it.”

The young Hurt had seen headlines about bad things happening in other communities. He had seen firsthand the devastating effects of 1969's Hurricane Camille in the Buckingham area, having helped take emergency supplies three years before to help those affected.

But Agnes changed the way he looked at the world.

“When it happens to you,” Hurt said, “it's eye-opening.”

Both darkness and light are all around.

Like a flood.