Mother Nature’s Garden: February is an in-between month

Published 5:06 pm Friday, February 23, 2024

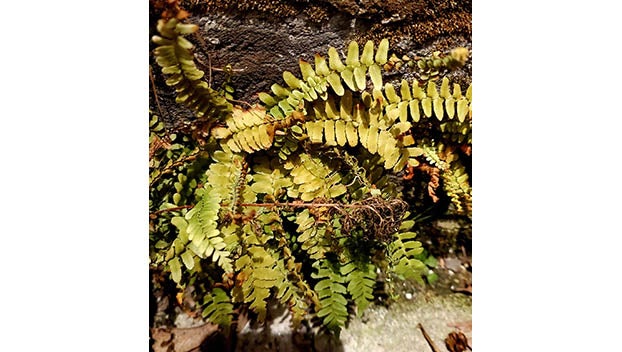

- Ebony spleenwort is epipetric and can grow on walls. Shining clubmoss prefers partially shady locations with lots of leaf litter.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

February is an in-between month for wildflower enthusiasts. It’s still winter, but there are glimmerings of life in the woods. The skunk cabbages are up and perfuming the air with their distinctive scent. Look carefully in sheltered areas, and you might find some round leaf hepatica. The spotted wintergreen looks rough, but it has survived the winter and will be ready to bloom in early June. There are even some dandelions blooming on hillsides and in the lawn.

It’s a good time to look for cranefly orchid (Tipularia discolor) leaves, which appear in fall, persist throughout winter, and then disappear in early spring. They have distinctive ridged fronts and beet red backs that make them easy to identify. Mark the locations of the leaves now and finding the delicate spikes of brownish blooms in late summer will be much easier.

Other plants to look for include the ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron) and shining clubmoss (Huperzia lucida). While ebony spleenwort is far easier to find, both plants are welcome splashes of green in February.

The ebony spleenwort gets its common name ebony from the dark, reddish black color of its stipe and rachis. Spleenwort refers to its use in traditional medicine to treat maladies related to the spleen. The ebony spleenwort is both terrestrial and epipetric, meaning it can grow in land and on rocks and rocky outcroppings. The sterile and fertile fronds are very different in appearance and habit. The sterile fronds are 2 to 6 inches long, have short, blunt alternate pinnae, and are evergreen; these are the fronds you’ll see now. The fertile fronds are 1 to 2 feet tall, erect, and have short, alternate pinnae below and larger, alternate pinnae above; the fertile fronds die in winter. The ebony spleenwort grows in old fields, clearings, mesic to dry forests, and various types of rock outcrops. It’s the most common Asplenium found in Virginia.

Shining clubmoss (or shining fir moss) is a descendant of the tree-like clubmosses that grew more than 400 million years ago and were 100 feet tall. They were one of the earliest vascular plants to evolve, and their remains helped form the coal deposits we find today. In spite of the common name clubmoss, this plant isn’t a moss; mosses aren’t vascular plants.

Shining clubmoss is an evergreen perennial that grows 3 to 8 inches tall and has light green stems that are sparsely branched. The leaves are glossy and narrow with small irregular teeth at the tips. The common name shining refers to the lustrous nature of the leaves. Shining clubmoss prefers dappled sun to light shade, as well as acidic soil with lots of organic matter. It’s usually surrounded by leaf litter. Although it’s more frequently found at high elevations in the mountains, shining clubmoss is widespread, if infrequent, in our area.

Yes, February can be a very frustrating month. Some days are quite warm, fooling us into thinking that spring has arrived earlier than usual. Other days are seriously cold, reminding us that winter is still here. Nevertheless, it’s still a great time to take a walk in the woods and search for plants.

Dr. Cynthia Wood is a master gardener who writes two columns for The Herald. Her email address is cynthia.crewe23930@gmail.com.