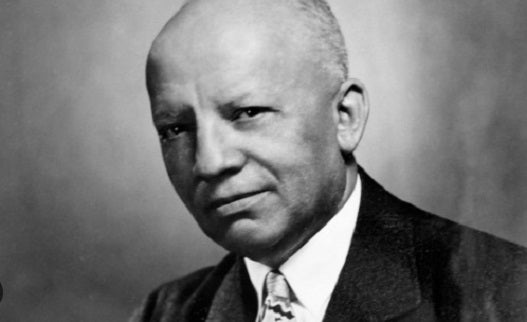

Carter Woodson: New Canton native shaped Black History Month

Published 7:09 pm Monday, February 19, 2024

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

He was a journalist, a historian and the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. He’s been called ‘the father of Black history’ and is the second African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard University. New Canton native Dr. Carter Woodson may not be the most recognized name, but there’s no denying his achievements or the role he played in establishing what would later become Black History Month.

According to Woodson’s own writings, preserved in the Library of Congress, the man believed it was critical to study and preserve Black history to avoid “the awful fate of becoming a negligible factor in the thought of the world.”

And in 1926, he organized the first Negro History Week, now celebrated each February as Black History Month, to encourage the study of African American history.

He wanted people to understand Black history in America, to make sure there was documented proof of both achievements and culture.

Carter Woodson: The early years

Carter Woodson was born on Dec. 19, 1875 in New Canton, to James Henry and Eliza Riddle Woodson, both former slaves. James Woodson, a carpenter and farmer, was also known for helping Union soldiers during the Civil War. His son Carter occasionally attended primary school in Buckingham County, when not needed on the farm.

When he turned 17, Carter left New Canton for Huntington, West Virginia with his older brother Robert Henry. The two boys went with the intent of attending Douglass High School, a secondary school set up for African Americans. But first, they had to earn money for living expenses. The two spent three years working in the coal mines on the New River, during which time Carter taught himself the basics of English and math.

According to the Library of Congress, at the age of 20, Carter entered Douglass High in 1895. The curriculum was supposed to take four years to finish. He earned his degree in 1897.

Very quickly after that, his career took off. For the three years after earning his degree, Carter worked as a teacher in Winona, West Virginia. In 1900, he was picked to become the next principal at his alma mater, Douglass High. For the next three years, he juggled work as a principal and classes of his own, driving the two hours between Huntington to Berea, Kentucky, where he was enrolled at Berea College.

In 1903, he earned a bachelor’s degree in Literature from Berea and he changed jobs. Carter became a school supervisor for the next three years in the Philippines before returning to the classroom in 1907. Carter attended the Sorbonne University in Paris and eventually Harvard University where he earned his doctorate in history.

Woodson continued his love of history and learning by holding educational and administrative positions in the Philippines, West Virginia State College and Howard University where he was dean of the School of Liberal Arts. These experiences would lead Woodson to discover the need for an emphasis on Black history.

Focusing on Black history

Being in the history and educational field, he noticed how Black history was often ignored and overlooked by teachings and textbooks. According to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), he was also prevented from attending American Historical Association conferences, even though he was a dues-paying member.

While he wanted to work as a Black historian, preserving Black history, Carter found no organization willing to work with him to make that happen. According to his letters, preserved by the Library of Congress, Carter found that Black history was “overlooked, ignored, and even suppressed by the writers of history textbooks and the teachers who use them.”

And so, the Buckingham County native created his own outlets to help push his mission forward. Carter went around and got support from several philanthropic foundations, then he launched the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915 in Chicago. Writing about his new project, Carter described the mission as the scientific study of the “neglected aspects of Negro life and history.”

But he wasn’t done. In 1916, he launched the scholarly Journal of Negro History, which is published to this day under the name Journal of African American History. Over more than 100 years, it has never failed to publish an issue. Despite going through two World Wars, the Great Depression, the Great Recession and multiple wars through the decades, you’ll always find the next issue of the Journal out on time.

Now from 1916 to 1925, Carter worked to grow and develop both projects, gaining recognition for his journal and the association. His letters show Carter was clear about the goal of building a “collection of sociological and historical data on the Negro, the study of peoples of African blood, the publishing of books in the field, and the promotion of harmony between the races by acquainting the one with the other.”

But something was lacking. He felt Black history needed some attention, something to draw focus on it. And so, he started looking at options.

In 1926, Woodson found a way to draw attention. He started Negro History Week during the second week of February as it aligned with Abraham Lincoln and Fredrick Douglas’ birthdays.

Leaving behind a legacy

Carter Woodson died on April 3, 1950, in Washington, D.C. However, he left behind over 30 books and the organizations he founded, including the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Associated Publishers Inc. and the Negro History Bulletin. It was these works along with the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s that led to the expansion of his Negro History Week to Black History Month.