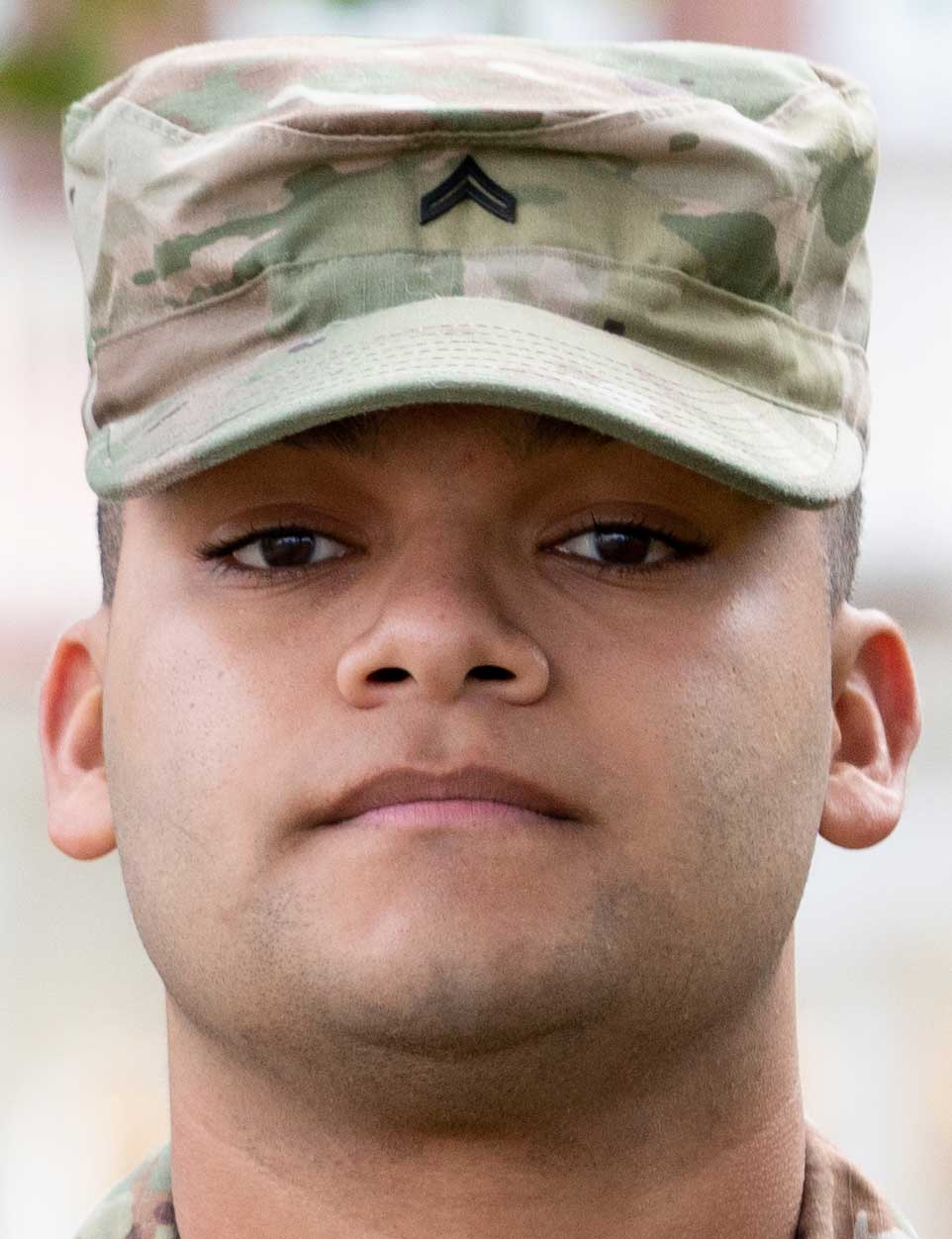

Marin is honored to serve

Published 11:05 am Wednesday, November 27, 2019

His first military funeral is etched in Marcus Marin’s memory, a Longwood University release noted.

There wasn’t a particularly large crowd gathered graveside, but it wasn’t particularly small either. And Marin, being inexperienced with the Honor Guard detail, was feeling nervous. He was focused on getting everything right as he looked in the restroom mirror, making sure his service cap, dress coat and white gloves were perfect.

So focused, in fact, that he almost didn’t notice the 6-year-old boy walk in behind him.

For many Honor Guard members, the moment they realize why they do it doesn’t come during the first service. It may not come until they’ve done a hundred. But that little boy said something that let Marin know he was exactly where he should be at that moment. It was something he could imagine his 6-year-old self saying to a veteran like the one he was about to salute.

“I want to be just like you when I grow up.”

Corporal Marin joined the National Guard the summer before matriculating at Longwood, the release noted. Neither of his parents had been in the military, but he felt called to serve.

“I didn’t find Longwood as much as Longwood found me,” he said in the release. “I could continue to perform my National Guard duties while at school, it was close enough to home that I had that support, and the program I wanted to pursue is very strong. It was a perfect fit.”

Marin, a psychology major who hopes to become a school counselor after he graduates in May 2020, has been on the Honor Guard for three of his four years in the National Guard, the release highlighted. The Honor Guard is a select group of guardsmen who are tapped to fulfill the solemn duty of attending Army veterans’ funerals and performing the familiar military ceremony. During the summers, he works full time on the team, and during the academic year, he still works on it part time, usually on weekends and holidays.

Officials said in the release that while at Longwood, he amazingly finds time to work in the admissions office while balancing his studies and his Guard duties, getting behind-the-scenes experience that will help him be effective as a school counselor.

“He’s one of my top student workers, always willing to help whenever I need him,” Longwood Dean of Admissions Jason Faulk said in the release. “Whether it’s filling in to lead a tour group, helping with large events or talking about his experiences as a student with waiting families, he’s always willing to pitch in. I know I can count on him.”

Done properly, it takes 13 creases to properly fold a flag to present to a soldier’s next of kin, the release noted. Each crease means something. The third fold honors the veteran, the fifth fold honors the U.S., the ninth honors the veteran’s mother and so on. When finished, the flag will be in a right triangle with no red showing, only white stars on a field of blue, the angles sharp and the edges straight.

Officials stated in the release that one Honor Guard member takes the flag — one hand on top, one hand on bottom — drops to a knee in front of the next of kin and speaks these familiar words:

“On behalf of the president of the United States, the United States Army and a grateful nation, please accept this flag as a symbol of our appreciation for your loved one’s honorable and faithful service.”

The full detail then performs a final salute, officials cited in the release. It’s the last honor for someone who served their country before they are laid to rest.

The release conveyed that it’s the same process every time — the same words, the same Taps, the same salute — whether there are 200 people standing silently graveside or no one has claimed the body and the only people present are two Honor Guard members and the funeral director.

“We do everything the same no matter who is there,” Marin said in the release. “There is no cutting corners or treating anyone differently. It’s about honoring their service to this country, and they all deserve someone to treat that with the most respect we can give them.”

This summer, the sun beat down on Marin as he picked up his side of the American flag from the soldier’s casket sitting in front of him. Taps hung in the air.

Marin and the other member of the Honor Guard began the prescribed process. The veteran’s next of kin sat to Marin’s right. Between the two guardsmen, they had done this ceremony hundreds of times before. Only this time, it was different.

“I can’t do this one,” Marin’s partner had told him before the service. “It’s too emotional.”

Marin knew what doing this one meant: presenting the folded flag to the mother. Unlike many military funerals Marin had performed, he knew much of the story of this soldier. He was in his mid-20s and had served four years, including in the Middle East, before coming home. Once home, he succumbed to the post-traumatic stress disorder that affects so many veterans.

“I turned to face the mother who was going to receive the flag, and something happened,” Marin said in the release. “I just started crying really hard. My shoulders were shaking as I gave her the flag, and the tears were just flowing down my face. I tried to keep my composure, but it was the hardest thing I have ever done.”

He doesn’t know why he broke down. Maybe it’s because the veteran in the casket was only a few years older than he was. Maybe it was the sorrow on the mother’s face. Maybe it was the emotion of hundreds of these moments coming to a crescendo. But in four years of performing military funerals — sometimes leaving class on a Friday afternoon to drive straight to a funeral home — Marin knew he’d never forget that moment.

But he still stood up and, shoulders shaking and chest heaving, gave the final salute.

“A lot of the people in reserves and guard units have a hard time finding their place,” Marin said in the release. “I was lucky that early on, the area coordinator for the Richmond Honor Guard thought I’d be a good fit for the team and encouraged me to join. Being in the Honor Guard gives me a sense of purpose. It’s my way of giving back.”

The Virginia National Guard Honor Guard comprises five teams across the state that perform honorary ceremonies at veterans’ funerals, the release cited. The ceremony ranges in size and scope — for soldiers killed in action or with at least 20 years of service, the Honor Guard will perform a gun salute, carry the casket, play Taps and present a flag to the next of kin. For all others, a team of two will perform Taps and present the flag.

“I know the Honor Guard technically means that we are honoring the veteran,” Marin said in the release, “but I also think of it as an honor for me to be there. It’s not lost on me that out of all the people in the armed services, I’m giving this veteran his or her final salute. That’s a big responsibility, and I take it very seriously.”