Values, rates vary across area

Published 12:00 pm Thursday, June 8, 2017

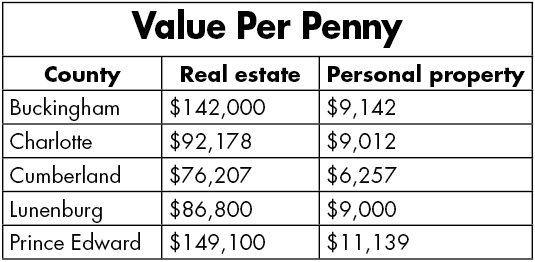

- The per-penny values of real estate and personal property tax rates show a wide disparity in the values across the Heart of Virginia.

Editor’s Note: Taxes allow local governments across the country to raise the funds needed to provide services to their citizens. But how much is enough? In today’s In-Depth Look, we compare the property tax rates of Buckingham, Charlotte, Cumberland, Lunenburg and Prince Edward counties and examine what those rates mean to you.

The rates levied on rural localities’ largest source of taxable property widely varies across the Heart of Virginia.

While Cumberland County has the fewest people living in its borders, it has the highest tax rate on real estate at 78 cents per $100 of assessed value. Lunenburg County, which has one of the lowest real estate tax rates in the state, has a levy of 38 cents.

Counties rely heavily on real estate tax collections to fund county operations, especially for public schools.

Buckingham’s real estate tax rate is 55 cents; Charlotte, 53 cents; and Prince Edward — the county with the largest population in the region — 51 cents.

Each year, during the fiscal year budget process, county boards of supervisors re-examine their tax rates — personal property (vehicles), merchant’s capital (business stock), machinery and tools (business equipment) and aircraft. For the most part, the real estate tax rate is the only rate supervisors will adjust, based on two main factors: funding for operational expenses and the reassessment of real property.

The Code of Virginia requires counties to conduct reassessments of land and homes once every six years. In the past 10 years, home and land values have fluctuated, which either increases or decreases what a county gets for its rate since it’s based on $100 of assessed value.

Boards of supervisors have the option of adopting an equalized rate, or one reflecting the new property values where the changed rate will bring in the same amount of revenue as the rate before the reassessment.

In Cumberland, one penny of real estate tax brings in about $76,207, whereas in Prince Edward County, one penny brings in about $149,100 — just $3,314 shy of double what Cumberland brings in per penny. This is because land and houses are worth much more in Prince Edward.

Buckingham gets about $142,000 per penny of real estate tax, while Charlotte gets $92,178. Lunenburg gets $86,800 per penny of real estate tax.

The assessed value of $100 on the rate shows the disparity in the values of land, according to the most recent reassessments.

Since 2012, real estate tax rates have slightly changed in each county. Cumberland’s rate has increased by 10 cents from 68 cents per $100 of assessed value, while Lunenburg has increased by two pennies from 36 cents to 38 cents.

From 2009 to 2010, Cumberland’s real estate tax rate jumped from 59 cents to 70 cents — an 11-cent jump in one year — but would eventually be reduced two pennies to 68 cents.

“If I remember correctly, we had a significant reduction in assessed values of property due to a once-every-four-years reassessment,” District One Supervisor Bill Osl, who served on the board at the time, said of the increase in a previous interview. “I believe the rate increase was to remain revenue neutral to the county.”

Since 2014, Buckingham’s rate has increased from 44 cents to 55 cents (11 cents), Charlotte’s has increased from 42 cents to 53 cents (11 cents), and Prince Edward’s has gone from 42 cents to 52 cents (10 cents).

Capital improvement projects, such as new schools and courthouses, reassessments of property, decreasing state funding and program reimbursement and increased costs are among the reasons local governments have used to justify increasing real estate taxes.

Economic activity and actions by the Virginia General Assembly also weigh heavily on a locality’s decision and ability to increase real estate tax rates, which makes it difficult for county administrators and county supervisors to predict how the rates on real estate could change.

“As of yet, none,” Buckingham County Assistant County Administrator and Finance Director Karl Carter said regarding a forecasted potential need for a tax increase in the next five years. The next reassessment will take place before 2020, Carter said.

Cumberland County Administrator and County Attorney Vivian Seay Giles offered no comment on the potential need to raise taxes in the next five years. “I have no comment about the boards’ decisions to change those rates through the years,” she said of the changes in tax rates over the years.

“There are no plans to increase the tax rates in the next five years,” said Prince Edward County Administrator Wade Bartlett.

Regarding the five-cent jump in real estate taxes in tax year 2015, Bartlett said the increase was “caused by changes in the (Piedmont) Regional Jail that caused the loss of several million dollars in revenues for the jail. This revenue loss caused the member localities for the first time (to) have to contribute to the operation of the regional jail. The loss of revenue was caused by two factors. First, when the ICE (Immigrations Customs Enforcement) Facility opened, the illegal immigrants that had been held by the jail were moved to that facility. This caused a loss of approximately $5 million in revenues. Second, the state reduced the amount of per diem they paid local governments by 57 percent from $28 per day to $12 per day. As I recall this caused an additional loss of $2 million in revenue.”

Bartlett said in an attempt to keep the member localities from having to pay for the housing of inmates, “for several years the jail board attempted to make operational changes to decrease expenses and seek ways to increase revenues. The jail board was partially successful, but not completely. For several years the jail spent down its fund balance until in FY14, the jail board had to come to the member localities and inform them the localities would have to begin paying a portion of the costs to operate the jail.”

Bartlett pointed to a real estate tax increase in fiscal year 2015-16 that was caused by “the fall in values during the reassessment, and is not classified as a tax increase because it did not increase the tax burden on the citizens when taken as a whole. In fact, the equalized tax rate would have been .51 cents, not .49 cents. The board of supervisors attempted to lower the tax rate, and in fact did for that one year, but due to increasing expenses, the board raised the rate for FY17 to .51 cents which was the equalized rate for the 2015 reassessment.”

Generally, personal property taxes bring in the second-most revenue in local taxes.

Cumberland and Prince Edward share the highest personal property tax rates in the area at $4.50 per $100 of assessed value.

The tax is assessed on personal property — such as cars, boats, motorcycles, trailers, buses and motorhomes — housed in the county during the tax year.

To assess the values of vehicles, most commissioners of revenue — the constitutional officer elected as the chief assessment officer for each county — use the NADA Blue Book. Other assessments of personal property are made on fair market value.

Rarely do local governments change their personal property tax rates. The most recent changes include Charlotte increasing its rate from $3 to $3.75 and Prince Edward increasing its rate from $4.20 to $4.50 in 2008.

Buckingham’s personal property tax rate stands at $4.05, while Lunenburg’s is at $3.60.

Per penny of its personal property tax rate, Prince Edward gets about $11,139, while Cumberland gets about $6,257.55 — again showing a wide disparity in the values of the vehicles in the two counties despite the localities having the exact same rate.

Buckingham gets $9,142 per penny, Lunenburg gets $9,000 and Charlotte gets $9,012.

This article has been corrected from the original edition.