Counties deal with addiction

Published 1:46 pm Friday, November 25, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The numbers keep shrinking and that’s not a bad thing. In Buckingham, Cumberland and Prince Edward counties, it’s no longer standard practice for doctors to prescribe opioids as a first resort. In fact, as some other Southside counties find their opioid problem growing, these three seem to be headed in the opposite direction. Now, as money starts coming in from opioid production settlements, it’s going to further help the counties clean up.

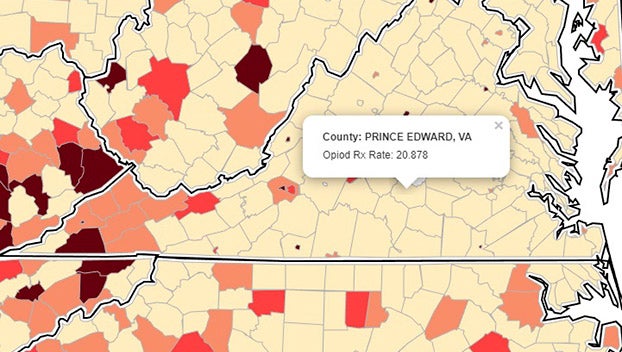

As of 2020, the latest data we have, an average of 43.3 opioid prescriptions were given out per each 100 people in the U.S. All of The Herald’s coverage area is dramatically below that figure and you can see a continuing drop with each. In 2019, 26.4 opioid prescriptions were given out for every 100 people in Prince Edward County. One year later, that had dropped to 20.8. In Buckingham, the number was 6.5 prescriptions in 2019, falling even lower to 4.4 in 2020. And Cumberland was the lowest of the three, with just 0.1 prescriptions for each 100 people.

“Much of this trend is due to increased caution by many providers in prescribing opiates or any controlled substance,” said Piedmont Health District Director Maria Almond. “Often, the preference now is for primary care providers to refer patients to a specialized pain provider, who balances the prescribing of opiates with other (alternatives).”

Almond pointed out there is a specialized provider in Prince Edward. That’s why P.E.’s prescription numbers are more than four times that of Buckingham and Cumberland. It’s just because that’s where the prescriptions are being given in the region. As we’ve spotlighted before, both Buckingham and Cumberland lack specialized medical care in multiple fields, which is why residents drive to Prince Edward for treatment.

Other areas struggle

By comparison, other parts of Southside and Central Virginia are still struggling. The city of Martinsville, for example, remains one of the top three areas in the nation in terms of opioid prescriptions, with 343.6 for every 100 people. The city of Lynchburg is the only other part in Virginia that comes close, with 104.5 prescriptions per every 100 people. Even the city of Richmond remains somewhat low, despite a much larger population, with only 55 prescriptions for every 100 people.

Now fewer opioid prescriptions is a positive, but it’s just part of the larger picture. While fewer prescriptions helps potentially lower the number of addicts in the future, local officials still have to deal with the existing addicts. Currently, for example, Prince Edward County has an annual rate of 26.1 deaths per 1,000 residents linked to opioid addiction.

There are also hidden costs related to addiction. The Virginia Department of Health partnered with Virginia Commonwealth University to launch an opioid cost calculator for cities and counties in Virginia. The tool looks at the loss of labor costs in the county, along with costs of crime related to addiction, state and local government costs and healthcare costs related to the problem.

To this point, the opioid crisis has cost Prince Edward County $7.4 million, with an ongoing annual expense of $342 per capita. In Buckingham, the number is $5.3 million, with $318 per capita and Cumberland has seen a cost of $2.6 million, with $273 per capita.

Now the good news is that all of those numbers are in the second-lowest tier in Virginia, highlighting that locally, the problem continues to shrink. With that being said, local officials are quick to point out the work isn’t over.

“Prince Edward, like most communities across the U.S., has had to deal with the rise of opioid use and overdose deaths over the past decade,” said Prince Edward County Administrator Doug Stanley. “Addiction impacts families and puts a strain on the support systems of the community. Addiction has also impacted crime rates in the community, as people turned to crime to feed their addiction.”

The Herald attempted to reach out to Centra Southside Hospital to talk about the impact opioid addiction has had on the support system, but were told they couldn’t discuss that. We would have to talk to Centra’s Lynchburg office instead. We contacted the Lynchburg office and were passed back to Southside.

How did this happen?

We talk about opioids, but how did this problem get started? For that, you can blame drug companies. Starting in the late 1990s, pharmaceutical companies marketed opioids heavily, claiming they were less addictive than regular pain medication. They sponsored medical-education courses, created ads and sent sales representatives to doctors, often giving free samples. As a result, in 2015, U.S. doctors prescribed three times more opioids than they had in 1999, according to the CDC.

In 2007 and 2020, Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty to misleading doctors and the public about how addictive OxyContin was. Company officials admitted that Purdue paid doctors through a speakers program, encouraging them to write more opioid prescriptions. They also admitted paying a medical records company to send information on patients to doctors as another way to encourage opioid prescriptions.

This fall, Virginia was part of another settlement, this time with opioid manufacturer Janssen Pharmaceuticals, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson ( J & J). The $99.3 million deal will see cities and counties receive funds over the next nine years. In addition, Johnson & Johnson agreed to stop selling opioids in the U.S. They also can’t promote opioids as a prescription or fund any other group that either promotes the drugs or legislation linked to them.

Money from that settlement is now being disbursed to the cities and counties across the state. While some of the money has to be spent on preventing future damage, most of it comes without strings attached. That’s left it up to local governments to decide where to use it.

Funds come

Now, to be clear, we’re not talking about millions of dollars here. Buckingham County, for example, received $20,674.84 from the J & J settlement and will get just over $7,000 more over the next nine years. Cumberland received $16,279.40 and will get just over $5,000 more during that time period. And finally Prince Edward received $30,930.87, with another $9,000 still to come.

Cumberland officials said they haven’t decided how to spend their money yet. In Buckingham, supervisors voted during their November meeting to let the finance committee come up with some suggestions on how to spend the funds. Meanwhile, in Prince Edward, the focus is on using the money to clean up the damage already done by opioids.

That’s happening in two ways. First, the county will work with the Piedmont Health District and Centra to help fund treatment and recovery programs. Second, the county is building interest in the region to create a drug court.

“This would provide an alternative means of dealing with addiction,” Stanley said. “Drug courts are specialized programs that divert non-violent offenders from incarceration and into treatment and rehabilitation.”

Currently, if someone gets arrested for substance abuse, they go to jail. Drug court instead offers them opportunities to attend classes or counseling, so they can change their behavior. If they comply, they don’t have to serve time. It’s also proven to work. Data from the National Institute of Justice shows recidivism, or repeat arrest, rates fall between 17% to 28% in areas with a drug court.

Stanley said he expects regional conversations about a drug court to take place in the coming year.

Brian Carlton contributed to this article.