Who monitors Virginia gold mining? It’s not always the state.

Published 3:31 pm Tuesday, August 30, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

DILLWYN – How do you effectively monitor a Virginia gold mining operation without the necessary resources or staff? It’s a question yet to be answered in Buckingham County, as well as several other areas of the Commonwealth. The problem is that while state agencies handle some issues, part of the regulation and enforcement falls to local governments, regardless of their size.

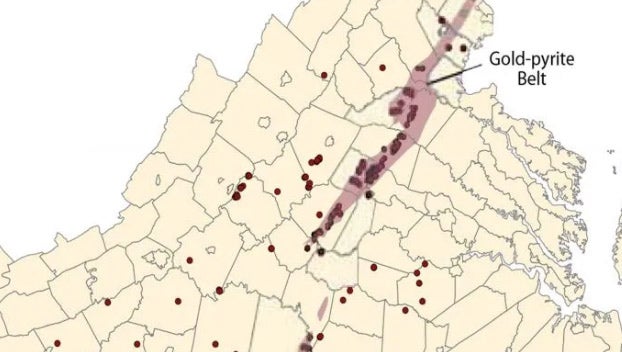

There are 427 active mineral mines across Virginia, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Some are just prospect mines, where a company isn’t sure what they’ll find. Others are occurrence mines, where you’ll only find a small bit of gold or iron in one isolated drill hole. And then there are the industrialized mines, the big operations. It’s up to local governments to design and enforce ordinances in each case. That means managing the mine’s impact on local traffic, mitigating noise levels, deciding hours of operation and land use zoning. But most of these Virginia gold mining operations are in small communities. Places like Buckingham County don’t have the manpower to do the job or the tax dollars to add more staff.

“We’re talking about a major operation and many counties that have small staffing in terms of local government, they just don’t have the bandwidth to understand these things and make sure (the rules) are followed,” said Jordan Miles. “It’s just not fair.”

Miles, the chairman of the Buckingham County Board of Supervisors, is part of a state study group designed to recommend changes to how Virginia regulates gold mining. He spoke Friday, Aug. 26, as part of a public hearing at the Buckingham County Community Center.

Virginia gold mining: order vs request

Another problem for Miles, other members of the study group and Buckingham residents in general is how the current laws and proposed ordinances surrounding Virginia gold mining are written. As of now, state law gives the Virginia Department of Energy the right to oversee most of what takes place on a mine site. But what it (and the proposed recommendation) also offers is a bit of a gray area.

For example, let’s say a company applied to mine gold. During the permitting process, the state only requires a groundwater withdrawal permit in specific circumstances. A company would also have to meet certain requirements before having to apply for a Virginia pollution abatement permit.

“Until we have a proposed project in front of us, we don’t know if the regulations are applicable or not,” James Golden told the group. Golden serves as regional director for the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality.

But for most people in attendance, Golden’s statement was the problem. They wanted the same regulations to be enforced for everyone. As another example, the document said “may be required” instead of “will be required” for many of the parts put in place for the permitting process. The concern is that companies could use the wording as a loophole, doing just enough to avoid having to enforce stricter regulations.

Why no fines?

Also, there are no fines involved, even if companies do violate parts of the permit. Members of the study group equated that to pulling someone over for speeding, but not giving them a ticket.

“Well heck, why should I not speed?” asked George Neall. The retired Rockingham County mining engineer questioned how likely it is that companies would obey the rules if there are no consequences for breaking them.

Michael Skiffington from the Virginia Department of Energy said in a case like that, his department would act as a traffic cop.

“(We) can reach in, take the keys and close the car down if we need to,” Skiffington said.

Several residents then asked if the department had ever actually done that, as in closing a mine down. Skiffington said he didn’t know.

People in the room also received an answer to the question of why the state doesn’t step in more, to help local governments regulate gold mining.

Study group member Suzanne Keller asked if Skiffington’s group actually has the resources to regulate gold mining, to monitor or “close the car down”, if need be.

“We very well may need additional resources,” Skiffington admitted.

How did we get to this point?

This issue stems from a situation that started more than two years ago. In April 2019, the Canadian prospecting company Aston Bay Holdings announced they were beginning to search for gold in Buckingham County.

To be clear, Aston Bay isn’t a mining company. It’s a prospecting company. That means they search for gold, silver or other minerals, identify and purchase a location, then sell that information (and property) to the highest bidder. They can do this because under Virginia law, prospecting doesn’t require a state permit if you’re searching for anything other than uranium.

In statements given in March 2019 and July 2020, company officials declared their drilling confirmed a “a high-grade, at-surface gold vein system at Buckingham, as well as an adjacent wider zone of lower-grade disseminated gold mineralization.” In other words, they found enough to keep going. At the beginning of 2020, the company has secured the right to prospect on 4,953 acres of land in Buckingham County.

But as of now, prospecting is all that’s happening. Skiffington confirmed there have been no applications to the Virginia Department of Energy to mine for gold. And he said his department isn’t aware of any activity or plans to do so in the near future.

Getting ahead of Virginia gold mining

Members of the General Assembly wanted to get ahead of the issue, however. That’s why Del. Elizabeth Guzman (D-Prince William) filed HB 2213 in 2021. The bill, which passed in that year’s regular session, put a few requirements in place.

First, a work group had to be set up to study the issue. The idea is to evaluate the impacts of gold mining on the area. The work group looks into the effects gold mining will have on the environment, including public health in general and the air and water quality.

Are existing regulations strong enough to protect air and water quality? Are there areas where mining needs to be banned? To answer those and other questions, experts in mining, hydrology, toxicology and other fields are being brought in. Also representatives of potentially affected communities in localities with significant deposits of gold are to be included. That’s what was happening on Friday.

After hearing from experts and holding public hearings, the group will put together a report by December. That will be discussed in the next General Assembly session, which begins in January 2023.

A gold mine owner’s perspective

Meanwhile, another member of the study group says they have plenty of time to get this right. In fact, he doesn’t expect to see any type of gold mining application anytime soon. Paul Busch owns Big Dawg Resources, running a gold mine in Goochland County.

The Buckingham County resident works to reopen old mines, remine the metals left behind and clean up the sites. That includes removing mercury contamination on the sites, reclaiming the shafts and removing underground timbers that have been leaching creosote into the groundwater. As a mine owner and mining engineer, Busch says he just doesn’t see enough to be concerned about an industrial mine.

“This state has been drilled since the 70s’,” Busch said. “No one has and no one will probably find a deposit large enough in this county to start an industrial scale gold mine.”

Aston Bay CEO Thomas Ullrich disagreed with Busch’s comments, pointing out that they are still very early in the process. We’ll have more from Mr. Ullrich, talking about a timeline for the project and where it currently stands, in next Wednesday’s edition.

What happens next?

There will be two more public hearings between now and November, both of which are currently unscheduled. The Virginia Department of Energy caught significant criticism for scheduling Friday’s meeting at 9 a.m., when so many people are at work. Even most of the study group had to call into the meeting, as they were either at work themselves or otherwise unable to make it in person.

Buckingham residents will also have a chance to speak about this at the next county meeting. The Board of Supervisors meets on Monday, Sept. 12. Sign up for public comment begins at 5:30 p.m.

Finally, if you’d prefer to give your thoughts on the issue from your laptop, you can email comments to goldstudy@energy.virginia.gov.