McAuliffe dedicates building in honor of Johns

Published 1:14 pm Thursday, February 23, 2017

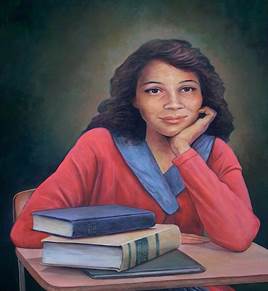

- Barbara Johns

Gov. Terry McAuliffe dedicated a newly renovated state office building in honor of civil rights pioneer Barbara Rose Johns on Thursday in Richmond.

The building, which houses the attorney general’s office, will not only bare Johns’ name, but a portrait of her inside, along with a plaque commemorating the naming.

The 16-year-old Johns led a group of students to walk out of the R.R. Moton High School in protest of the dilapidated conditions in 1951, paving the way for a lawsuit that led to the desegregation of the nation’s public schools.

“Barbara Johns didn’t simply lead her classmates in a protest of inequitable schools,” said McAuliffe in a press release issued by his office. “She led a group of young people and an entire nation to realize that courage was blind to age and race, and that real change requires action. The walkout she led kicked off an extraordinary chain of events that eventually invalidated the deception of ‘separate but equal.’ Having her name placed among the other giants in Virginia and American history who are celebrated on Capitol Square is a fitting tribute to her legacy.”

“This has been such an exciting time. The dedication of this building is beyond anything that we could ever have dreamed of. And we were so excited and ecstatic over the whole thing,” Joan Johns Cobbs, Barbara’s sister who joined her in the walkout, said after the event. “And we are so pleased that Gov. McAuliffe decided to name this building after our sister. It is just a wonderful, momentous time and we are very grateful for his thoughtfulness and his generosity.”

“The dedication ceremony for the Barbara Johns Building was full of excitement and great energy,” said Cameron Patterson, managing director of the Robert Russa Moton Museum and Civil Rights Landmark. “It was great to be in the presence of so many Virginians who recognize the impact of … Johns and the need for her important contributions to our nation’s history to be shared with a wider audience.”

He said the naming of the building in honor of Johns “will serve as a powerful reminder to all Virginians that all of us have the ability to create positive change when it is rooted in fairness and justice.”

“Working in the Barbara Johns Building will be a daily reminder to me, my team and all those who pass through our doors that we must commit ourselves every single day to the pursuit of justice,” said Attorney General Mark Herring, who joined McAuliffe at the dedication and whose offices are housed in the building. “Barbara Johns showed our commonwealth and our country that progress is not always easy or inevitable. It requires courage and leadership, often from a young person who can still see injustice with clear eyes.”

“It’s hard to find words to express how we feel, but it’s wonderful. It is an exciting time in our life because we have been through a lot … This seems to be the culmination of a lot of good things that have happened since she has passed,” Cobbs said.

“I don’t think I’ve come down yet,” said Joy Cabarrus Speakes, who marched with Johns, calling the event “such an accomplishment and achievement.”

Though it may have been a long time coming, Speakes said naming the building “was right on time. And just to think that Gov. McAuliffe thought enough to take that building and name it the Barbara Johns Building. I am just so thankful and I think this is going to give so much more exposure to the leader that Barbara was and what came out of Prince Edward County.”

“We were before Martin Luther King or Rosa Parks or any of those … We led the Civil Rights Movement, if you think about it,” Speakes said. “It was a long struggle to get what she set out for … If I had to do it all over again, I would do the same thing.”

According to the press release, “the classically-styled building originally was constructed as the Hotel Richmond, one of the city’s first high-rise buildings and an epicenter for Richmond and Virginia politics during the first half of the 20th century.”

“The hotel housed the winning campaigns of five governors between 1945 and 1965 and was the home of Richmond’s first radio station, WRVA, for three decades. The state purchased the building at 202 N. Ninth Street in 1966 and converted it into office space, renaming it the Ninth Street Office Building.”

“The event yesterday was celebratory but also deeply admiring of the pioneering actions taken by Barbara Johns and her fellow students,” said Dr. Larissa Fergeson, the university liaison between the Moton Museum and Longwood University. “People recognized that while we have come a long way, there is still much to do to fight for equality for all Virginia citizens.”

According to the release, McAuliffe and the Johns family unveiled the plaque that will hang in the building; a portrait of Johns will adorn the grand lobby.

The student-led protest came after Johns became frustrated by her school’s overcrowding and poor conditions and by the school board’s refusal to build a new high school comparable to the county’s school for white students.

“On April 23, 1951, the high school junior led more than 450 of her classmates as they walked out of the school and marched to the courthouse and to the homes of local school officials to protest unequal conditions,” officials said in the release. “The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) sent civil rights lawyers Oliver Hill and Spotswood Robinson to Prince Edward County to meet with the students, and they agreed to file a lawsuit, Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, in federal court on their behalf. (Dorothy E. Davis, daughter of a local farmer, was the first name on the list of students wishing to file suit, hence the case bears her name instead of Johns’.) The Supreme Court later combined its ruling in the Davis case with four other similar cases in what became the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision that declared segregation in the nation’s public schools unconstitutional. Rather than obey a court order to integrate its schools, Prince Edward County closed all public schools from 1959 until 1964.”

Fearing reprisals against their daughter for her part in the student strike, Johns’ parents sent her to Montgomery, Ala., according to the release, “where her uncle Vernon was serving as pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. She lived with her uncle’s family while she completed high school and then studied at Spelman College in Atlanta for two years.”