Reducing cancer in cosmetics

Published 5:36 am Thursday, August 4, 2016

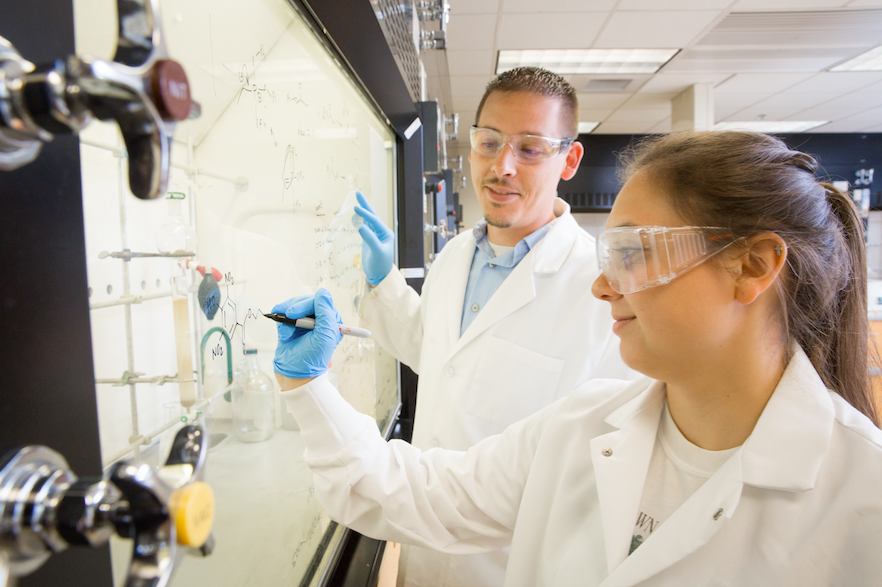

- LONGWOOD UNIVERSITY Longwood student Bridget Bergquist and professor Dr. Andrew Yeagley review changes to a paraben structure.

Bridget Bergquist slowly poured silica gel, sand and liquid into a glass tube, then watched everything trickle to the bottom. The rising Longwood University senior was extracting an anti-bacterial compound, one of several she has developed, from a reaction to get it ready for testing.

It’s part of a process she’s repeated twice every day this summer during a research project which one day may save lives, according to a Longwood press release.

The future pharmacist is changing the chemical structure of parabens — preservatives used in cosmetics — to see if their innate bacteria-killing ability can be maintained while disabling their ability to mimic estrogen, which can be a factor in breast cancer.

The results of Bergquist’s research are promising. At least 11 of the 15 compounds she has developed and biotested have been found to kill bacteria.

“We were surprised to find that halogens, especially iodine, seem to be important in killing bacteria, though we don’t know why,” she said.

Dr. Andrew Yeagley, the faculty mentor in the project, believes the findings are an important step in fighting cancer.

“We’re pretty sure that this modification will stop parabens from causing breast cancer but will not keep them from killing bacteria,” said Yeagley.

Another benefit of the project: Bergquist, a chemistry major from Bristow, is greatly enhancing her skills as a scientist and gaining experience for her future career.

“This research has allowed me to see how a drug is made or improved. It’s like research and development,” she said. “I’ve been able to apply what I’m learning in my chemistry classes, which is interesting. I’m also learning biology. One thing I’ve learned is a new term, ‘inoculating,’ which is adding bacteria to something on purpose. We’re putting bacteria in a liquid to see if the compounds are killing bacteria, then we try to kill the bacteria.”

Bergquist also has learned about a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometer, which tells her whether each of the compounds she develops is “clean” enough — free of other substances — for testing.

“I had used the NMR in class, but this project has taught me the importance of it — why and how it’s used,” she said. “I’ve also learned how to interpret the data, which comes out in graphs with peaks. Now I know what’s a clean graph and what isn’t clean. The standards for a clean compound are higher here than in class. I really like the satisfaction that comes from a clean NMR.”

The paraben project is part of ongoing research by Yeagley, who, in working with Hailey Kintz (’17) during the 2015-16 academic year, found a change to the paraben structure he said “turns off parabens’ ability to cause breast cancer.” Bergquist’s experiments this summer, which eventually will yield more than a dozen compounds, are an effort to shed more light on that promising discovery. This fall, Bergquist will continue her research under Yeagley and Dr. Amorette Barber, a cancer cell researcher.