Documenting a father’s faith

Published 10:13 am Thursday, April 21, 2016

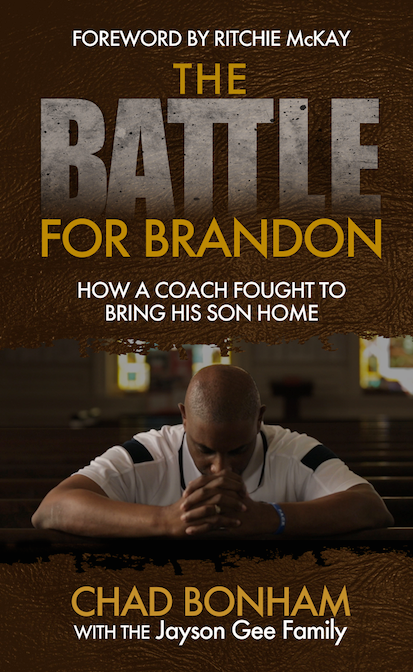

- A new private trailer for “The Battle for Brandon” has been made as well as the draft for the book’s cover.

By Halle Parker

The Rotunda

Schizophrenia is a complex mental illness that creates a constant state of confusion for the person, characterized by delusions, hallucinations and strange behavior.

According to the World Health Organization, the incurable disorder causes complications in the minds of over 21 million people worldwide, and over 50 percent do not receive the appropriate care.

But it is treatable.

Twelve years ago, Longwood head men’s basketball coach Jayson Gee’s eldest son, Brandon Gee, was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia at 11 years old and spent three years in various medical facilities receiving treatment.

Over the three years, Brandon was non-responsive as he was given a variety of medicines, each with different effects. Brandon said medical professionals considered him a vegetable during this period, aside from his volatile outbursts from time to time.

Simultaneously, Gee was beginning his budding coaching career in Division I men’s basketball as an associate head coach at St. Bonaventure and Cleveland State. Despite Brandon’s inability to communicate during this period, Gee balanced his coaching duties with traveling over an hour and half to and from Brandon’s facility for visits lasting ten minutes on a good day.

Doctors and close friends told Gee to let go of his son, considering him a lost cause to the incurable mental disorder. But Gee pushed through the fog of doubt surrounding the situation.

After three years, Brandon emerged from treatment as a functional 14-year-old, proving his father’s efforts worthwhile.

“He would just pray over me, tell me I would be healed, and then one day, I was,” said Brandon, looking at his father.

The idea of a film was planted in Jayson Gee’s mind about eight years ago. Outside of being an associate head coach at Cleveland State, he spoke to different teams at chapel services about his family’s journey on the side, delivering their message of perseverance, love and faith in the face of adversity.

“This story has been such an inspiration and this is before we even thought about it being a book or a movie or a documentary and so everyone we tell this story to is significantly inspired and so to know that I’m a part of that is encouraging,” said Gee.

According to Gee, person after person would walk up after his visits and tell him the story needed to be on the big screen. One of the most important people to push for the rise of the Gee story was a friend and eventual executive producer, Joey Holland, the owner of several car dealerships in West Virginia.

“Joey Holland is the guy that has really underwritten all this and I would say he’s probably spent close to $100,000 by now, so his name’s worth mentioning,” said Gee with a laugh.

Holland’s willingness to fund the endeavor fueled even more life into the cause. The pair had a screen-worthy story and the money to create it, but lacked the writer to bring it all to life.

Then, last year, the final element found its way into the equation. After winning the John Lotz Barnabus coach of the year award from the Fellowship of Christian Athletes’ (FCA) last April, Gee was approached by a young writer with the perfect background in co-authoring books dealing with sports and religion.

After listening to Gee’s story, sports journalist Chad Bonham, recognizing the powerful message and miraculous plotline placed before him, didn’t hesitate.

“It really is on all levels a miraculous story that kind of unfolded with this family,” said Bonham. “I usually go looking for stories or go researching for stories, but when you get a phone call one day and someone says, ‘Hey here’s a story you need to hear about and here’s some people that want to make it happen. That doesn’t happen everyday and it’s just been a blessing to be a part of this.”

With Holland’s financing, Bonham began working to make the concept of a movie a reality using a documentary and book, targeting not only faith-based audiences, but a wider spectrum of viewers.

“This has a broader message in that this is what it looks like when a family doesn’t give up hope, this is what it looks like whenever a dad fights through the doubt and fear and the negative reports, this is what happens when love overcomes all of these impossible scenarios. And that’s a big message. That’s a big message that can appeal to anyone,” said Bonham, the director of the documentary and author of the novel, both titled, “The Battle for Brandon.”

For the past year, the team of Bonham and the White Wolf Creative production company headed by Paul Lawson, a friend of Bonham, collected interviews from a variety of perspectives including Brandon’s doctors, other basketball coaches, family friends and countless others.

While documentaries tend to move faster than feature films, Bonham explained hiccups can still occur and prolong the typical 12 -14 month development. “The Battle for Brandon” has yet to hit a snag.

“With this process, everyone was so interested in helping tell the story that we had virtually no problems getting people to come on board,” he said, aside from the family giving the different doctors permission to talk about Brandon’s condition during his three years in their care.

The core of the story remains within the dynamics of the Gee family, including his wife, Lynette Gee, youngest daughter, Briana, and his middle son, Bryan Gee, who also plays at Longwood under his father. Each played a different role during treatment and have seen their roles evolve in the time since as more stories, experiences and individual feelings have been expressed through the interviews.

According to Bryan, who was nine years old when his brother was diagnosed, sharing more about the experience has continued to strengthen the family. The Longwood guard said, “I know from my family members it brought up a lot of things that weren’t originally shared or known by other family members.”

“It did bring up some new things, some old things that happened and we’re kind of still dealing with it,” said Bryan. “But I think it’s made our family stronger.”

Jayson Gee noted the willingness of his family to relive that time, considering how traumatic the period was for not only Brandon but all of the Gee’s, demonstrated their progress in accepting those lost three years and the ongoing recovery since then.