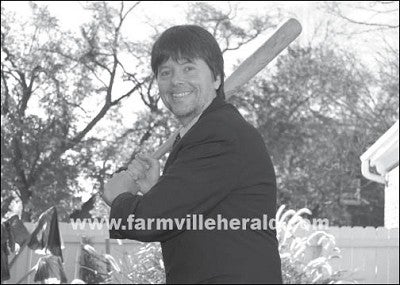

Ken Burns' Love Affair

Published 4:30 pm Thursday, November 25, 2010

HAMPDEN-SYDNEY – Ken Burns loves baseball so much that decades into his soul-deep romance with the sport he cannot pass even a neighborhood little league game without slowing his car long enough to see the next pitch.

But the award-winning film-maker, whose 20-plus hours long documentary Baseball is an audio-visual Bible of the sport, broke up with the national pastime once, left baseball standing alone at home with its diamond but without his glove.

Going to college in the wake of the 1960s can do that to a young man's heart and turn his head inside out.

“I, because of the counter-culture, I fell out of baseball,” he said during a recent interview prior to his keynote address at the inauguration of Hampden-Sydney College president Dr. Christopher B. Howard.

Falling out of baseball.

Like falling out of love.

Describing baseball as a place, a hallowed space that once held the Brooklyn-born Burns, who grew up in Michigan and was a fan of the Detroit Tigers, a team that gave him his first World Series thrill in 1968, the Al Kaline and Mickey Lolich-led team topping Bob Gibson's St. Louis Cardinals.

“The Tigers were my team,” he said.

Were.

Was.

Baseball, for time, lived in his past tense.

Burns fell out of baseball like Adam and Eve fell out of a different kind of paradise.

The documentarian knows what he missed during that dark night of the baseball-less soul.

The 'Miracle Mets,' for one thing, something most Brooklyn-born baseball fans savored as heart balm after the westward flight of their beloved Dodgers a decade earlier.

“So '69, the Mets victory, was just a public interest news story to me-the underdogs won; '70, '71, '72 are sort of black holes for me,” Burns said, sounding much like Kevin Costner's character in Field Of Dreams. “I was at college, I didn't care, I just thought it was a manifestation.”

A what?

Though Burns fell out of baseball, baseball hadn't fallen out of him.

Not entirely.

Baseball loved him still and was there waiting for him to return some day.

Some day came during the 1972 season, the last year of his black hole, when he visited the home of one of his Hampshire College professors in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Fatefully, her husband had a television set on.

Faithfully, it was baseball, waiting to embrace Burns once more.

A moment of soul's awakening?

Thirty-eight years later, Burns can even remember the precise model and make of television set.

“Her husband had just bought a color TV, a Sony Trinitron, and it was just like 'Wow,' and he was watching the baseball game,” Burns recalls, “and I remember I sat down and I go, 'I love this game. Why did I leave it? Why did I leave it?.'”

Speaking of baseball as if it were something-or someone-to whom he'd once said, 'I do.'

Of all the professors' houses in all the world, he'd walked into theirs.

It was the stuff that dreams are made of.

Burns soon fell head over heels for the Boston Red Sox, for it was they who graced his moment of epiphany in front of the television set.

“And it happened to be the Red Sox. I was in New England and it happened to be (Carlton) Fisk, and (Jim) Rice and (Fred) Lynn, Luis Tiant and Bill Lee,” he said. “And it was just a team to fall in love with and care about.”

And a sport to fall back in love with and care about.

“And that's been it, and I've lived in New England ever since so it is my local team,” Burns said, as if needing to explain where the Detroit Tigers went in his life.

Baseball and Burns.

Until death do they part.

“Baseball's such an amazing sport. Each new game erases everything that went before it, as much as it contains the ghosts and echoes of every, every single game that's been played before,” he said.

Burns will film an Eleventh Inning addition to his Baseball series, which just saw the Tenth Inning debut this fall, and he already knows how that film will begin. With Detroit Tigers pitcher Armando Galarraga and umpire Jim Joyce. The pitcher who threw a perfect game during the 2010 season, except that the umpire called the 27th batter safe at first. Mistakenly, as Joyce quickly acknowledged and apologized for profusely.

And Galarraga? He never lost his temper. Threw neither temper tantrum nor bat nor ball.

Just an out-of-body smile crossing his face, and then back to the mound to retire the next batter.

A perfect game that wasn't.

Burns calls it a perfect game. Twice. Intentionally.

“I already know how I'd start it, with Armando Galarraga's perfect game. That would be the prologue, Armando Galarraga's perfect game,” he said, giving the signs for his next pitch.

The Galarraga-Joyce moment, and its aftermath of forgiveness and human grace, are evidence Burns is willing to submit to any prosecuting counsel arguing that another sport is America's game.

“To me it was just the proof, if we need to defend ourselves, that the National Pastime is the greatest game that's ever been invented. And I try, all the time,” Burns said, beginning his great litany, “to tell people all the other sports go up and down the field or the rink. With all of them the object is to get the ball into something…

“All the others have clocks. There's no clocks here,” he says, using “here” as if baseball, again, were a place and a space out of time. “Here the defense always has the ball. In no other sport does the defense have the ball…The fields are all different. What if I told you my gridiron was 105 yards…or I've got an oval basketball court? While the infield is rigid and we look at those numbers like the Golden Mean, the outfields are all different, we allow for that.”

Next comes an insight one may not have heard articulated so clearly. Or at all.

“And then, in some ways the most important thing, is that you can't play your best player every time. You can't inbound to Michael Jordan to hit the three-pointer at the buzzer. Your middle infielder who is hitting .215 might come up when the whole game, the whole season, is on the line; you just can't move people around in the line-up.”

In football, he noted, “You know that Joe Montana's always going to throw to Jerry Rice.”

Baseball's a democracy. Every player gets their turn to swing the bat, regardless of the pressure or importance of the moment.

“I love that about the game,” said Burns.

And how about that look on Galarraga's face when he turned, the tide of ecstasy rising up his face at having pitched a perfect game, to see Joyce call the runner safe?

“That smile is, to me, along with Mona Lisa's smile, it's one of those inscrutable beautiful things where you realize the essence of sport-it's just a game,” said Burns. “It's just a game.”

But what a game. What a monumental “just.”

“And every parent of every little leaguer must have had a sigh of relief,” Burns said of Galarraga's reaction, “because the lesson in sportsmanship was just so phenomenal.”

Human nature argues for a ballistic reaction from Galarraga.

“Totally ballistic,” Burns agrees. “If it had been football…”

He doesn't finish the sentence. It wasn't football.

Football isn't baseball.

Only baseball has grown up with America so much that the sport can tell the history of the nation, Burns points out. “It really just mirrors (U.S. history)-immigration, race, and labor and management,” he said. “And all of these themes.”

Baseball is the only sport that cannot let Burns pass even the most pedestrian game-if there is such a thing-without slowing down to see what might appear, like magic, next.

“I can drive through a residential area and there's a game going-softball, little league, hardball-and my foot eases up on the accelerator,” Burns said, “and I turn, I turn back and forth, waiting for that pitch, just the pitch.”

Anything can happen.

Nothing is impossible.

The ball can go through Buckner's legs.

Or the Red Sox can become the only team in history to come all the way back to win a seven game series, which they famously did in 2004 against the archrival New York Yankees, after trailing three games to none.

“There's something happening,” Burns said, reaching out into the mist, the starlight and the firmament. “It's possibility.”

Around the corner of the neighborhood in a sandlot pick-up game or at Fenway Park.

“So it tells you that it can be at any kind of level that you want. I, of course, have sat in front of TV sets and paced until Keith Foulke got a come-backer and threw it underhand to Doug Mientkiewicz and we had beaten THEM, you know. We had won,” he said, reliving the thrill of victory over the 2004 Yanks.

Just as he knows the agony of defeat can quite as easily hit the cut-off man and throw utter joy out at the plate.

Or Aaron Boone can simply hit a Bucky Dent-esque home run to topple towers, sand castles and any hope of keeping cold and darkness at arm's length through the long winter.

Boone and Dent share the same middle name among Red Sox fans, by the way.

Bleeping.

Aaron “Bleeping” Boone.

Bucky “Bleeping” Dent.

Sons of Bronxers, both of them.

Ask Burns if there is a lost game that still pains the wound and he immediately responds.

“Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah.

“The two worst, well, the three worst for me are Bucky Dent and the Sixth Game of the '86 series,” the latter game the one in which the ball eluded Buckner, the final nail in a coffin of mistakes, bad decisions and you-name-it by the Red Sox.

“But in some ways, because it's still fresh and because I had to edit it in great detail and it's a really good scene (in the Tenth Inning) is on Aaron Boone's home run,” Burns said, before recounting the night of agony like some kind of helpless Paul Revere and the Yankees had figured out some third unstoppable way-not by land or by sea-to crash Boston hopes, so forget the lanterns in the steeple of The Old North Church.

All the lights went out for Burns in those hours after sunset.

“I had given a speech in Massachusetts that night,” he recalls. “It was the 16th of October, 2003. I was getting married on the 18th. Remarried on the 18th. And I was driving home and I was listening to the game and then I was in central Massachusetts and I lost the game on a pretty poor car radio.

“And I would call my wife when I had cell service and she goes, 'We're ahead.'

“She grew up in New York a Yankee fan, converted to Red Sox. She says, 'We're ahead 5-2, it's okay, it's the eighth inning.'

“Then I lost the cell for her and lost the radio completely.”

Heading home in the dark, figuratively and literally.

Darkness all around, not just at the edge of town.

“I drove into my drive-way and I knew something was wrong and she came out and she goes, 'They're tied.'

“And I said, 'Oh no, we've lost.'

“She goes, 'No, no, they're just tied. They can win.'

“I said, 'No, you don't understand.'”

And they didn't.

And she didn't.

But Aaron “Bleeping” Boone did.

The Red Sox lost.

Julie Burns felt the fingertips of comprehension, like the grip on the pitch you wish you had never thrown.

As Boston writer Mike Barnicle said in the Tenth Inning regarding that game's aftermath, Burns recites, “when the baseball season was over, it's time to put the storm windows up.”

Darkness is outside, playing catch with the bitter cold.

And there are no gloves warm enough for any Red Sox fan.

But there are sunlit memories that glow like embers in a deep-banked fire despite the falling snow of the baseball-less season.

Like the Opening Day at Fenway Park when Burns took his daughter, Sarah, to the game.

“We skipped school,” he said, admitting his accessory before, during and after the fact. “We went…”

On an educational field trip.

“Exactly. It was a whole day. We were way out in left field and we quickly fell behind 7-2 going into the ninth inning…against the Mariners and we came back and won it on a walk-off grand-slam by Mo Vaughan,” Burns said of the consecrated moment. “And a third to a half of the people had left…and we hugged people we didn't know…”

Joy cometh in the bottom of the ninth best of all.

The greatest moment for Red Sox fans, of course, was the curse-breaking 2004 World Series triumph, the first since 1918 and what Burns had been living for, and dying a little bit, too, each season. Chicago Cubs fans shouldn't worry that their relationship with the Cubbies will be diminished by finally grabbing baseball's Holy Grail with both hands. It won't.

“You know, that's what everybody assumed would happen,” Burns said of what many thought would happen to Red Sox fans-that making the dream come true would somehow take a little bit of the dream away in seasons to come, that baseball in Beantown wouldn't matter quite as much. “That there would be some diminution of interest in the Red Sox, but I find it exactly the opposite.”

Describing his feelings, Burns steps into the sunlit stained-glass cloisters of theology that speak of that great gift of God's love that we cannot earn, but are given nonetheless.

“What I do find is an unexpected kind of grace,” Burns said of a team that was once known as The Pilgrims prior to becoming Red Sox.

That one ironic, future-telling, fortune-predicting name fit all sizes of Red Sox fans during that long pilgrimage from 1918 to 2004 and for Burns the journey had begun on that fateful day at the professor's home in 1972.

“I don't get as angry or worried. Maybe not angry, but worried,” he reflects on the resonating aftershocks of that 2004 destruction of the Curse of the Bambino. “…My overall sense was, I told my wife the second they won that I didn't have to worry again.”

Passion can be a complicated pool of moonlight at midnight, or dawn.

“I worried again,” he said, after pausing just a beat to emphasize the words.

And quickly.

“I worried again the first time they started losing the next season,” Burns said.

“But it's less. And there's more even-temperedness. But the love is no less the same. I go to more games and it's more exciting. Fenway is sold-out for years and years and years. It's just an amazing experience to be there.”

As a man whose own films on baseball must assuredly win him a place in Cooperstown, what Hollywood movie swing connects for the winning hit atop his favorite's list?

The betting going into the question-even though betting is illegal in baseball; a rose by another name doesn't smell as sweet-was that Field Of Dreams or Bull Durham would be starting, with the other warming up in the bullpen to close it out.

“Oh yeah. Far and away I think that Bull Durham is because it gave you a lot of baseball, it gave you a lot of inside baseball. They did it with humor. It's sexy. You had a sense of the business of the sport. It didn't succumb to the sentimentality and nostalgia that are the enemies of all baseball films,” he said.

“I turned to her and said, 'Oh, yeah, what is it about?'

“She said, 'It's about belief.'

“I said, 'Oh yeah, so what's ET about?'

“She goes, 'Oh, friendship.'

“I suddenly went, 'My God, this is the Holy Grail here. She gets it.'

The baseball doesn't roll far from pitcher's mound.

“There is a lot of sentimentality and nostalgia in Field Of Dreams. For the most part it works. But what I think elevates Bull Durham is just its human realism and the characters seem familiar, even as they are, in some cases, written as caricatures. I mean, Nuke LaLoosh is just an over-the-top character. You'd never meet anybody that dumb or the assistant coach that Robert Wuhl plays with his (gobbledy-gook talk) but it all comes together, it works. And a lot of that is a testament to the writer/director Ron Shelton,”

Burns said, tipping his cap.

If Burns could go into Field Of Dreams' mystical cornfield and interview someone from baseball's past it would be Jackie Robinson and Ty Cobb. What one game from baseball history would he choose to attend? April 15, 1947. The great Robinson's first game, carrying not just a uniform number on his back, but a bull's-eye, too, along with an entire race and the future of American society at virtually every level.

No athlete has ever faced such pressure.

“I can't think of anybody, and in a game in which pressure can kill,” Burns said. “…How was it possible to do what he did?

Robinson broke far more than the modern color barrier in the game of baseball.

“This is one of the great stories of all humankind,” Burns said of Robinson, about whom he will dedicate a future documentary. “It's not a baseball story.”

Burns said “the centrality of race in the United States” was what he learned most filming the original Baseball series.

“And that, in a sport like ours, that the most important moment could be Jackie Robinson's arrival…The way that baseball is such a precise mirror of America really surprised me. At the beginning, we thought we were doing this sort of antidote to the killing in the Civil War,” he said, referring to another of his landmark documentaries, the Civil War series.

“And we woke up very early on and realized we were engaged in the sequel to the Civil War, that if you wanted to know what post-Civil War United States history was,” he said, “you could find no better thing than baseball to try to tell the story. That was surprising.”

What jumped out of the Tenth Inning was an “understanding of how to tolerate contradiction, to not jump to facile judgments,” Burns said regarding baseball's steroid controversy. “We've always tried to do that and understood that lifting up the rug and sweeping out some of the dirt didn't in any way diminish the quality of the tapestry, but only set it in greater relief…But it required a greater act of will here because it's contemporary and we all love to make decisions: 'Oh, Barry Bonds, he's really bad.' Barry Bonds is the greatest player we've seen, probably, in our lifetimes…but he made some choices and he will forever drag along the ball and chain of the steroid scandal.

“We had to understand that he was a human being and just because he's been caught or in the spotlight doesn't mean that even our most favorite players have not done it also,” the film-maker said.

The Tenth Inning also accurately portrays the excitement and joy of the summer of 1998 and the race by Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa to break the 61 home run season record of Roger Maris.

“Pedro really helped us out on that,” Burns said, of Hall of Famer-to-be pitcher Pedro Martinez who was interviewed and appears in the Tenth Inning. “…He had that comment that 'innocence is beautiful sometimes.'…He did understand that there is that innocent love of the game and then there is the facts, the cruel facts, of the business.”

And the steroids.

“So I think when he says 'innocence is beautiful' it permitted us to go back and re-enjoy and re-invest ourselves with all we remember,” Burns said, recalling stopping off at a bar in Colorado in the summer of 1998. “I was just passing a bar and I stopped and went in and McGwire was up and I just wanted to watch…and I wanted people to remember that, but also remember the Andro.”

With the Eleventh Inning's prologue set, should the Chicago Cubs finally win a World Series, in the meantime-for Cubs' fans it has been a mean, mean time-that miracle would find a big part of center stage.

“The Cubs would certainly galvanize that…And one hopes this can be detailing the extraordinary career of Stephen Strasburg. And obviously,” he said, noting the necessary concatenation of weather conditions, “the Cubs winning the World Series would be one of those 'hell freezes over' moments.”

The San Francisco Giants finally winning the World Series will also take its place in the next installment of Burns' Baseball.

“In the week or so since the World Series ended I've gotten so many emails from people saying 'It was so interesting to watch the Tenth Inning to suffer through the tribulations of the Giants, particularly the devastating defeat in 2002 against the Angels.' And to feel that somehow you helped them through this time and a lot of people have been doing that…and so we sort of thought, 'Wow, we've already got something,” he said, having believed nobody could beat the Philadelphia Phillies this year.

“And the Giants wrestled it away and made it their season. And that's what's extraordinary about baseball,” Burns said. “And fortunately the play-offs are long enough that this isn't a fluke. They earned it. They earned it.”

The Giants, though 2010 World Series champions, had a pitching staff that harkened back a century to the New York Giants of Christy Mathewson, who in 1905 pitched three complete game shut-outs in the World Series in six days.

Six days is less than a week.

Obviously.

But Mathewson's unrepeatable feat is so astonishing that the obvious can appear to be a ripple of heat mirage above the pavement.

Tim Lincecum, he of the temporal distortion wind-up, leads the Giants pitching staff and is someone Mathewson would recognize as a brother-in-arms.

“You think about, the number four starter was (Madison) Bumgarner and you're going, 'Wait a second' and you had (Matt) Cain but Lincecum is really something else,” Burns said. “We spotted him a few years ago and threw him into the outro of the Tenth Inning because he's something special. And it's good to see, like in the tradition of a Pedro Martinez, somebody who's small and looks like another human being, not as the kind of Roger Clemens Transformer, is such a dominant pitcher.”

For some fans in the 57-year old Burns' generation, who grew up watching pitchers that all had wind-ups, Lincecum takes them back to their childhood, makes them feel like a kid again, watching the game.

They are not alone.

“Yeah, and his is such a little league wind-up. It's almost as if, I remember I was pitching a couple of games in little league and a friend of mine's father took me aside and he said, 'Okay, I want you to throw a change-up'

“And I said, 'I don't know what a change-up is.'

“He goes, 'Well, all you do is pretend like you're going to throw it really hard and then just let it go easy.'

“So I remember having this exaggerated Lincecum sort of anger as if I'm about to drill you with this ball and then sort of eased up a little bit and of course they were swinging way ahead. And it was the worst example of a change-up,” he says with a smile, “but I love seeing Lincecum. He reminds me like I'm on the little league field.”

Ghosts and echoes all around.

Falling in love with the game.

And then leaving one day.

Or so you think.

When Burns gave his heart to baseball as a child, baseball gave its own heart to him in return.

Innocence is beautiful.

Baseball's heart was there all the time, beating inside Burns even when he turned and looked the other way with determined indifference.

A manifestation of life.

As the next pitch is on the way and anything is possible.